There are many metaphors for patent prosecution, each one with its own subtle twist.

Take, for instance, a one-sided tennis match where the odds are heavily stacked in favor of one player—the patent office. Patent prosecution is like a tennis match between the patent applicant and the patent office, one in which the office has the upper hand and cannot lose. Every time the applicant serves (read: files the application) the office takes its time to generate its return. For every return by the patent office (read: office action), the applicant has to do everything, within a limited window of time, to address what comes with it—objections. If the applicant fails to return satisfactorily, or returns beyond the allocated time, it's game over. This back-and-forth may stretch over multiple exchanges, but the underlying theme remains unchanged: strict deadlines and obligations are in place for the patent applicant, and failure to meet them results in rejection.

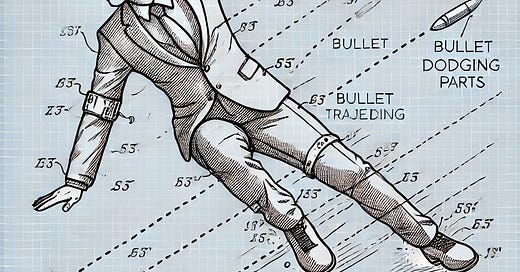

Some may prefer the gunfight analogy over the tennis match as it resonates better with patent law: we know that the "life" of a patent is for 20 years unless cut short by revocation or invalidation and we have prior art that can "kill" the novelty of an invention. If you look at it from the lens of a gunfight, then patent prosecution can be seen as an exercise in dodging bullets—every objection in the office action is like a bullet that can harm your invention. And patent prosecution itself can be seen as the art of dodging bullets.

Dodging Bullets

A gunfighter (read: applicant) must constantly maneuver to avoid being hit by a bullet. Dodging the bullets fired by the patent office can take different forms: the applicant may give up part of the invention through amendments or narrow down the scope of the claim or try to differentiate the prior art cited in the objection (like saying "the prior art teaches away from the invention"). All these maneuvers are essentially efforts to dodge the bullet. They are efforts made after the fact to salvage the invention. There is nothing preemptive about dodging bullets.

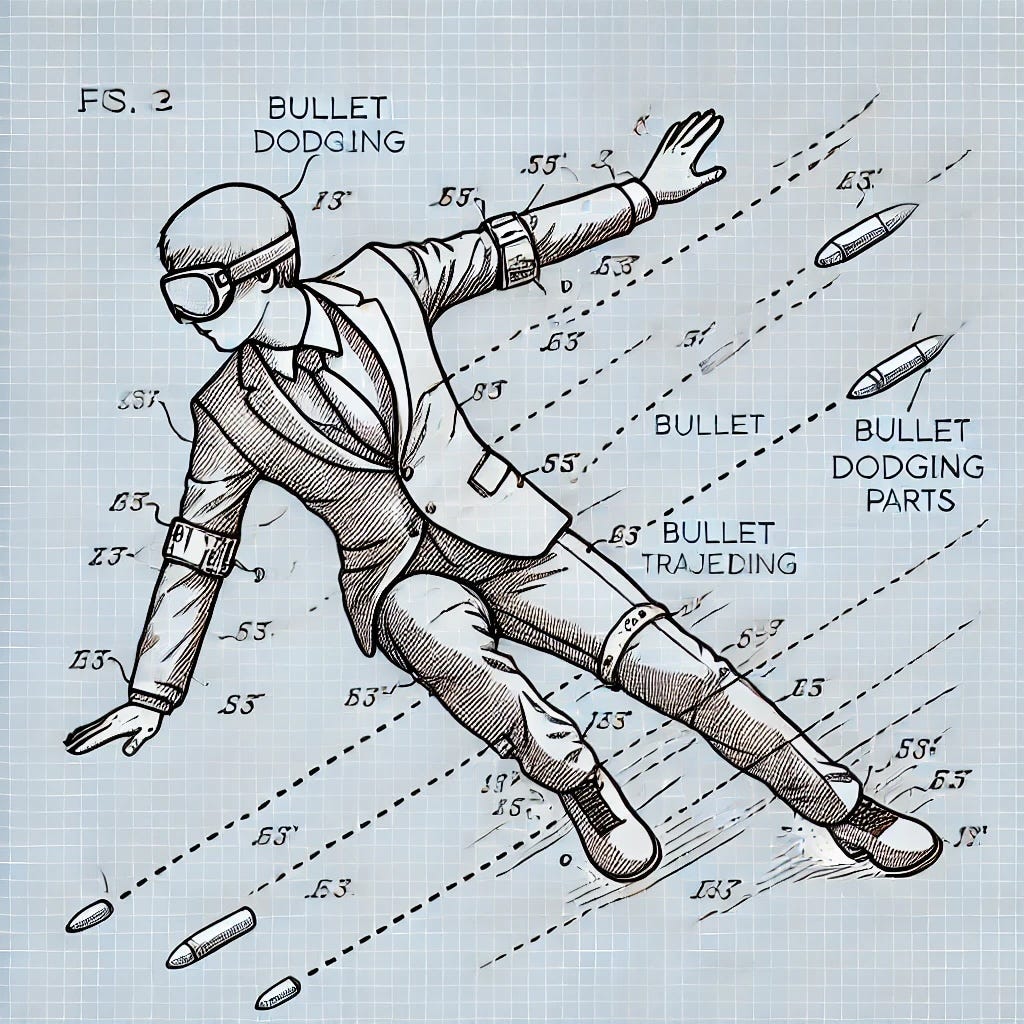

Bulletproofing

The gunfighter has an alternative enabled by modern technology. She can bulletproof the invention. She can draft a bulletproof patent that protects the unique value in the invention, addresses all the requirements and preempts office objections. The approach of drafting bulletproof patents is a preemptive strategy that is quite different from the reactive approach of dodging bullets. This strategy involves completely satisfying the requirements at the patent office (which is at times overlooked while filing an application) and predict the office objections that can come and prepare in advance to avoid them.

There are two broad approaches in patent prosecution when faced with an office objection. The first approach is to argue your way out (by interpreting the legal provision, by distinguishing the invention or by differentiating the prior art) and the second approach is to file an amendment to avoid the objection, where it is possible to do so. Bulletproof patents follow a third approach. It uses technology to predict objections.

AI is Prediction Technology

AI is all about prediction and anticipation. Al analyzes large datasets to learn patterns and the forecasts future outcomes or responses based on probabilistic models. AI-supported screening methods in radiology has already made headlines by detecting 29% more cases of breast cancer compared to traditional screening methods. A well-trained AI model that has access to the web may identify a prior art match within minutes. If such a technology is ubiquitously available to everyone—to the applicant and the patent office alike—the game of prosecution will move away from identifying prior art (as it is today) and shift toward bringing out the unique value in the invention.

In the book, The Age of Prediction, the authors say that traditionally prediction in a complex non-linear system has been nearly impossible as these systems behave randomly. With the prior art comprising of all the knowledge in the world, the patent systems should qualify as a complex non-linear system. The books then says that it is no longer true:

So, what has changed? Three things: the accelerating growth in computing power—driven mostly by Moore’s law, which describes the doubling of capacity for every generation of semiconductors (roughly every 18 months); the explosively exponential growth in data (especially genomic data); and the development of increasingly sophisticated analytical processes using machine learning and AI. The algorithms can now model all of the data to continually improve the predictions, and it doesn’t matter which aspect of the data or metadata creates the improved model. All data is fuel for the prediction. In time, the powers of prediction will be central to almost all our activities and products.

The power to make predictions is enabled by the combination of better computing power, big data and AI. If better predictions can eliminate possible objections, we may well be moving towards an era of bulletproof patents.

The article presents a powerful and practical idea. Comparing patent prosecution to a tennis match and a gunfight makes complex concepts easy to understand. The difference between "dodging bullets" and "bulletproofing" is well explained—prosecution is not just about responding but about preparing in advance.

The key insight is how AI can predict objections and help create "bulletproof patents," making the process faster and more effective.

Thanks to Feroz Ali Sir for explaining this so clearly and brilliantly!

Dr Alok Gupta

Patent Agent

Muzaffarnagar (UP), India